Costa Rica’s 2018 elections: the two Alvarados, between deepening division and democratic dependability

The two contenders in Costa Rica’s presidential runoff on 1 April 2018, Fabricio Alvarado (PRN) and Carlos Alvarado (PAC), are diametric opposites on the issues that have dominated recent elections, and their supporters are also divided along geographic and socioeconomic lines. Thankfully, a healthy democratic context militates against the worst effects of polarisation, write Evelyn Villarreal Fernández (State of the Nation Programme) and Bruce M. Wilson (University of Central Florida).

Before Costa Rica’s elections on 4 February, it was already clear that no candidate would reach the 40% vote share required to take the presidency and avoid a runoff on 1 April.

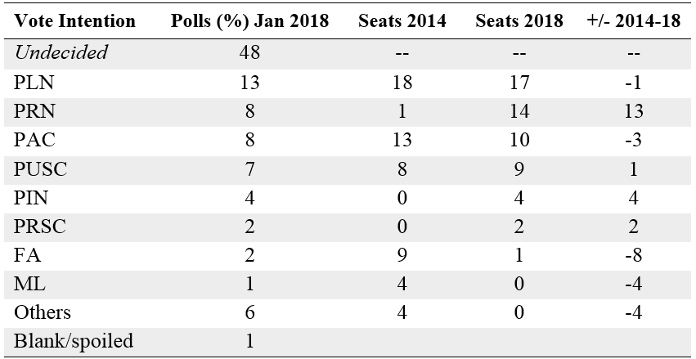

As late as one week before the election the volatility of voter preferences and the sheer number of undecided voters made predicting even which two parties would contest the second round very difficult (see Table 1, below). For the same reason parties themselves found it hard to identify their main rivals and to strategise against them.

The combustible context of the first-round vote

Election season began in traditional Costa Rican fashion, with parties focused on the dominant issues of corruption, security, and development; little attention was paid to “moral issues”.

All that changed four weeks from election day when the InterAmerican Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) issued its favourable decision on Same Sex Marriage (SSM) and Transgender Identity. The campaign suddenly became a referendum on SSM, with scant attention paid to any other issue.

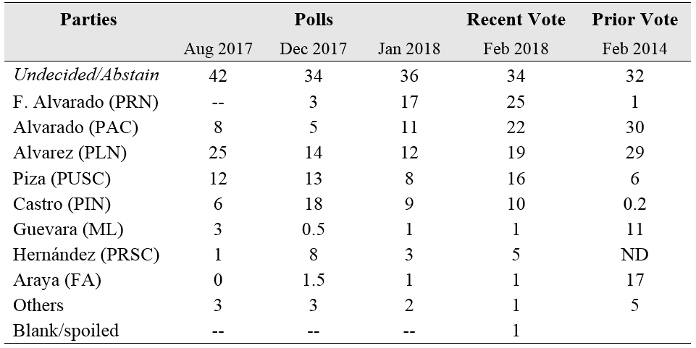

The right-wing evangelical singer, pastor, and former deputy Fabricio Alvarado (PRN, pictured left) jumped from nowhere in the polls (October 2017) to become the leading candidate in the final poll (January 2018).

Following a campaign focused on overturning the IACtHR decision and taking Costa Rica out of the Inter-American Human Rights System, he ultimately took almost 25% of the presidential vote, with his party also adding nine seats to become the second largest party in congress. Three smaller evangelical parties fielded presidential candidates, but Alvarado’s PRN swallowed up the evangelical vote in both races

The incumbent party’s candidate Carlos Alvarado (right), meanwhile, promised to respect the IACtHR ruling, legalise SSM, and continue the policies of the current government: this positioned the two parties as diametric opposites.

Since 1953, elections in have been run by the Supreme Electoral Court, a quasi-fourth branch of government that has successfully conducted free, open, and fair elections.

While turnout has declined from approximately 80 percent before the 1998 election, it has settled at about 65%. But national numbers obscure significant regional differences and a major geographic imbalance: half of all voters reside within 5% of the national territory, and mainly in the urban areas around the capital city, San José.

Although the PRN appears to have captured most of the country’s voting districts, it was generally weaker in the more populous areas of the Greater Metropolitan Area, and this may affect the second round. PRN support, meanwhile, is strong in poorer areas and much weaker in more affluent areas.

A renewed and gender-balanced congress

Twenty-five parties fielded candidates for congressional elections, but only seven parties captured at least one seat (see Table 2).

Of these seats, almost 44% are occupied by women, which is the highest total in Costa Rican history. And because deputies are prohibited from seeking immediate re-election, all 57-members of the Legislative Assembly are elected in parallel with the presidential elections, which tends to mean a great many “freshmen” deputies. 90% of the new cohort have not previously served in congress.

As expected, five parties split the bulk of the vote by receiving 10% or more of the vote, with no party garnering more than 25%. This set up a second-round contest between right-wing evangelical Fabricio Alvarado (PRN) and Carlos Alvarado of the centre-left PAC, though together they received less than half of all votes cast (with a turnout of 66%).

Contrasting candidates and democratic dependability in the second-round runoff

The runoff vote will take place on 1 April, Easter Sunday, which is likely to affect turnout.

If the campaign moves away from its focus on SSM, voters will see very different proposals and priorities: PRNpresented a 34-page general plan that focuses on moral issues – “values and family” – but also social and inequality policies. PAC’s plan runs to 101 pages and focuses on poverty reduction, inequality, and environmental issues.

But the future President Alvarado, be that Fabricio or Carlos, will have difficulty pushing his agenda through congress: neither party enjoys a majority, and parties are in any case famously undisciplined, leading to much unpredictable voting.

On a positive note, even without immediate reelection of deputies, voters appear to be holding political parties to account. In the case of Movimiento Libertario (PML), whose candidates were directly linked to the recent Cementazo scandal, voters removed the party from its remaining four seats in congress. Likewise, Frente Amplio appears to have been punished for its proximity to the current government, losing eight of the nine seats it held in the 2014-18 congress.

Moreover, despite high levels of uncertainty, a fragmented party system, claims of electoral fraud, and the injection of religion into the heart of the elections, the electoral authorities demonstrated their strength in the first round by quickly and decisively resolving most issues, thereby creating conditions for an uncontested result that all of the candidates could accept.

This is all the more important in such an unstable situation, and it bodes well for the second-round runoff in early April.

Artículo original del blog Latin America and Caribbean Centre. The London School of Economics and Political Science disponible en: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/latamcaribbean/2018/02/08/costa-ricas-2018-elections-the-two-alvarados-between-deepening-division-and-democratic-dependability/